Source(google.com.pk)

Types Of Sharks Biography

To wrap it up, let's look at some of the types of sharks we've been discussing.

ANGEL SHARK:

•flat body like a stingray -- you can tell the shark is not a ray because the pectoral fins are not attached to the head.

•They bury themselves in the sand or mud with only the eyes and part of the top of the body exposed.

•They are bottom feeders, eating crustaceans like clams and mollusks and fish that are swimming close to the ocean floor

BASKING SHARK:

•second largest shark (about 30 feet long and 8,000 pounds)

•filters plankton from the water using "gill rakers"

BLACKTIP REEF SHARK:

•does well in captivity so is often found in aquariums (which is why we have so many photos of it)

•about 6 feet long.

•grey with a black tip on its fins and white streak on its side

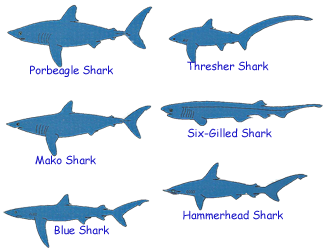

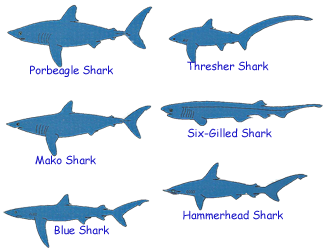

BLUE SHARK:

•about 12 feet long.

•sleek, tapered body

•among the fastest swimming sharks and can even leap out of the water

•diet consists mostly of squid, but it will eat almost anything

•considered dangerous - have attacked people

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

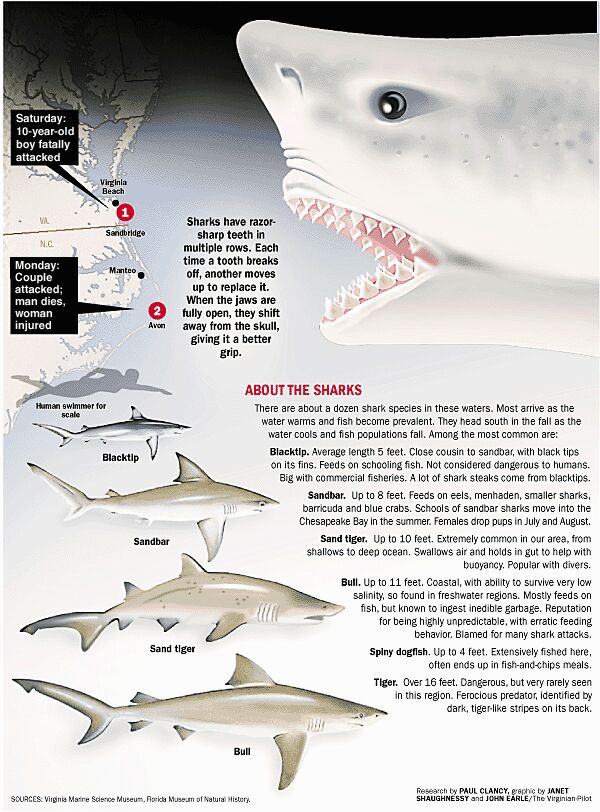

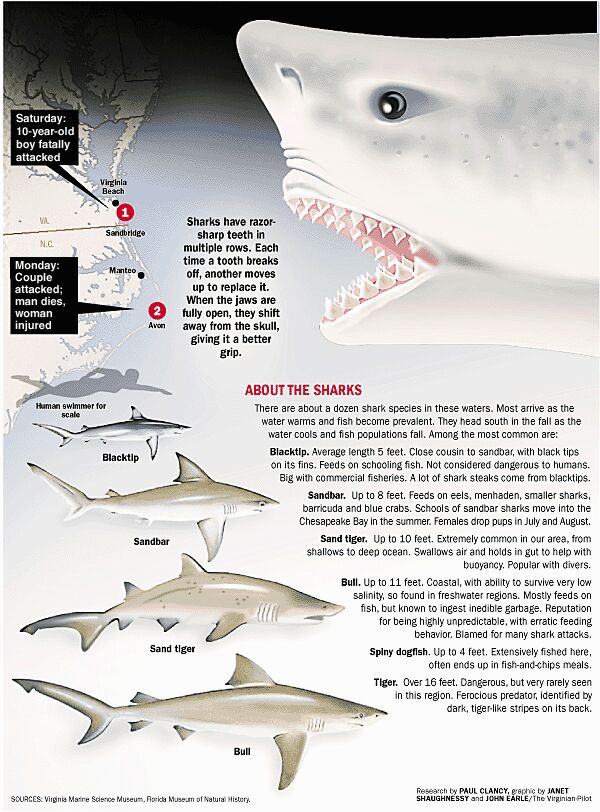

BULL SHARK:

•third most dangerous to people

•can swim in salt and fresh water and have even been found in the Mississipi river.

COOKIECUTTER SHARK:

•a small shark (less than 2 feet long)

•eats perfecty round chunks out of living whales and dolphins by clamping its teeth extremely sharp teeth onto them.

GOBLIN SHARK

•very uncommon and likely the strangest looking shark (rarely seen the photos were actually taken in 1909)

•pale, pinkish grey skin with a long pointed snout (it looks a bit like a sword on top of its head)

•lives in very deep water.

•found off the coast of Japan in 1898... until that time it was believed to have been extinct for 100 million years

GREAT WHITE SHARK:

•more attacks on people than any other type.

•averages 12 feet long and 3,000 pounds.

•unlike most sharks, it can lift its head out of the water.

HAMMERHEAD SHARK:

•unlikely to attack people, but considered dangerous due to its predatory nature and its size

•eyes and nostrils are far apart, giving it a "hammerhead" appearance and allowing the shark to extend the range of its senses.

MAKO SHARK:

•fastest swimmer (43 miles per hour)

•known to leap out of the water (sometimes into boats

NURSE SHARK:

•bottom dwelling shark

•thin, fleshy, whisker-like organs on the lower jaw in front of the nostrils that they use to touch and taste

•hunt at night, sleep by day

•common at aquariums

SANDTIGER SHARK:

•the sandtiger shark has very pointed teeth -- the better to eat you with (if you're a fish!)

•10 feet long

•predator (carnivore)

•nocturnal (hunts mostly at night)

•Babies: The mother shark has two uterus. Many sharks begin in the uterus, but the strongest one in each uterus eats all the others before they are born.

SPINY DOGFISH SHARK:

•the most abundant shark

•3 to 4 feet long

•slightly poisonous spines (not very harmful to people)

•used by people for food and research.

THRESHER SHARK:

•10 foot tail (1/2 as long as the body) which it uses to herd small fish

TIGER SHARK:

•second most attacks on people

•eat anything! (have been found with boat cushions and alarm clocks in their stomachs)

WHALE SHARK:

•biggest shark and biggest fish

•it isn't a whale (whales are mammals, not fish)

•grow to 45 feet long and 30,000 pounds, but average about 25 feet long

•filters plankton from the water using "gill rakers"

WHITE TIP REEF SHARK:

•probably the most common shark encountered by divers and snorkelers on tropical reefs

•about 3 feet long on average though it can be as big as 6 feet.

•dark grey with a white tip on the first and sometimes on the second dorsal fin as well as the tail lobes

Photo by Yvonne

WOBBEGONG SHARK:

•about 8 feet long, but virtually harmless.

•lives in Australia and Pacific coastal reefs

•lies on the bottom of the ocean waiting for fish to come near.

•filters food into its mouth with worm-like projections on its head

•razor-like teeth

•yellow, brown and gray camouflage colouring.

ZEBRA SHARK:

•small, gentle shark that can be kept in an aquarium with other fish

•tail is half its length

Types Of Sharks Biography

To wrap it up, let's look at some of the types of sharks we've been discussing.

ANGEL SHARK:

•flat body like a stingray -- you can tell the shark is not a ray because the pectoral fins are not attached to the head.

•They bury themselves in the sand or mud with only the eyes and part of the top of the body exposed.

•They are bottom feeders, eating crustaceans like clams and mollusks and fish that are swimming close to the ocean floor

BASKING SHARK:

•second largest shark (about 30 feet long and 8,000 pounds)

•filters plankton from the water using "gill rakers"

BLACKTIP REEF SHARK:

•does well in captivity so is often found in aquariums (which is why we have so many photos of it)

•about 6 feet long.

•grey with a black tip on its fins and white streak on its side

BLUE SHARK:

•about 12 feet long.

•sleek, tapered body

•among the fastest swimming sharks and can even leap out of the water

•diet consists mostly of squid, but it will eat almost anything

•considered dangerous - have attacked people

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

BULL SHARK:

•third most dangerous to people

•can swim in salt and fresh water and have even been found in the Mississipi river.

COOKIECUTTER SHARK:

•a small shark (less than 2 feet long)

•eats perfecty round chunks out of living whales and dolphins by clamping its teeth extremely sharp teeth onto them.

GOBLIN SHARK

•very uncommon and likely the strangest looking shark (rarely seen the photos were actually taken in 1909)

•pale, pinkish grey skin with a long pointed snout (it looks a bit like a sword on top of its head)

•lives in very deep water.

•found off the coast of Japan in 1898... until that time it was believed to have been extinct for 100 million years

GREAT WHITE SHARK:

•more attacks on people than any other type.

•averages 12 feet long and 3,000 pounds.

•unlike most sharks, it can lift its head out of the water.

HAMMERHEAD SHARK:

•unlikely to attack people, but considered dangerous due to its predatory nature and its size

•eyes and nostrils are far apart, giving it a "hammerhead" appearance and allowing the shark to extend the range of its senses.

MAKO SHARK:

•fastest swimmer (43 miles per hour)

•known to leap out of the water (sometimes into boats

NURSE SHARK:

•bottom dwelling shark

•thin, fleshy, whisker-like organs on the lower jaw in front of the nostrils that they use to touch and taste

•hunt at night, sleep by day

•common at aquariums

SANDTIGER SHARK:

•the sandtiger shark has very pointed teeth -- the better to eat you with (if you're a fish!)

•10 feet long

•predator (carnivore)

•nocturnal (hunts mostly at night)

•Babies: The mother shark has two uterus. Many sharks begin in the uterus, but the strongest one in each uterus eats all the others before they are born.

SPINY DOGFISH SHARK:

•the most abundant shark

•3 to 4 feet long

•slightly poisonous spines (not very harmful to people)

•used by people for food and research.

THRESHER SHARK:

•10 foot tail (1/2 as long as the body) which it uses to herd small fish

TIGER SHARK:

•second most attacks on people

•eat anything! (have been found with boat cushions and alarm clocks in their stomachs)

WHALE SHARK:

•biggest shark and biggest fish

•it isn't a whale (whales are mammals, not fish)

•grow to 45 feet long and 30,000 pounds, but average about 25 feet long

•filters plankton from the water using "gill rakers"

WHITE TIP REEF SHARK:

•probably the most common shark encountered by divers and snorkelers on tropical reefs

•about 3 feet long on average though it can be as big as 6 feet.

•dark grey with a white tip on the first and sometimes on the second dorsal fin as well as the tail lobes

Photo by Yvonne

WOBBEGONG SHARK:

•about 8 feet long, but virtually harmless.

•lives in Australia and Pacific coastal reefs

•lies on the bottom of the ocean waiting for fish to come near.

•filters food into its mouth with worm-like projections on its head

•razor-like teeth

•yellow, brown and gray camouflage colouring.

ZEBRA SHARK:

•small, gentle shark that can be kept in an aquarium with other fish

•tail is half its length

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

Types Of Sharks

%20for%20coral%20reef.jpg)